Photos by Stephanie S. Cordle

Via Maryland Today / By Karen Shih ’09

“I want everybody to be a children’s advocate,” said Associate Clinical Professor Brandi Slaughter in the School of Public Policy. “Kids are lost in the discussion. They don’t have lobbyists like the AARP. They don’t vote. But they deserve advocates that are just as trained.”

As director of the Karabelle Pizzigati Fellows Initiative in Advocacy for Children, Youth and Families since 2021, she’s equipping undergrads from across the University of Maryland with the skills to get heard, supported and funded in the crowded halls of Congress. They are placed with a children’s advocacy organization, where they receive a stipend for working 120 hours, and take a policy class that teaches everything from data analysis to how to engage families, policymakers and nonprofit organizations.

Slaughter draws on her own experiences. Her family used public assistance when she was young, and after college, she returned to her home state of Ohio to serve families in need. She started out running an after-school program for high-risk youth at settlement houses before earning a law degree and pivoting to policy, working for legislators and advocacy groups.

“Kids only have one childhood. We have to make sure we are providing programs, systems, investments to ensure that childhood is the best that they can have. Because we know on the other end what happens if we don’t,” said Slaughter. Abuse and neglect, parental substance use and domestic violence are linked to chronic health problems, substance use issues and more in adulthood, stunting educational and work opportunities.

Slaughter shares how a snowy fall led to her career as a children’s champion, why she takes the fellows to a Terps women’s basketball game every year and the galvanizing speech from a century ago that still resonates with her.

Framed food stamp

“I personally know what it means to rely on programs like Medicaid and food stamps,” said Slaughter, recalling her childhood in West Virginia and Ohio. “Most people don’t know what it means to go to a register and have to pull out an alternate form of payment. It’s embarrassing.”

Today, food stamps are no longer paper slips but rather on cards, making it easier for people who use them to make purchases unobtrusively; this was an administrative but transformative policy change, she said.

“I keep it because it reminds me where I’ve come from,” she said, pointing at the food stamp on the top row of her bookshelf. “It fuels my activist spirit.”

______________________________________________________________________________________

The “G-Force”

The postcard was given to Slaughter by Gayle Channing Tenenbaum, the godmother of advocacy for health and human services in Ohio, known as the “G-Force” for her ability to convince both Republicans and Democrats to pass legislation.

A chance meeting with Tenenbaum transformed her career. Slaughter had slipped in the snow and was hobbling on crutches at the Ohio Statehouse, where she worked for a state senator. When she stepped into an elevator, Tenenbaum said, “Girl, what did you do to yourself?” To her surprise, Tenenbaum not only recognized her but offered her a job lobbying for youth in foster care. “She told me she’d been following my career. To have her think that much of me, because she’s so legendary, was amazing.”

______________________________________________________________________________________

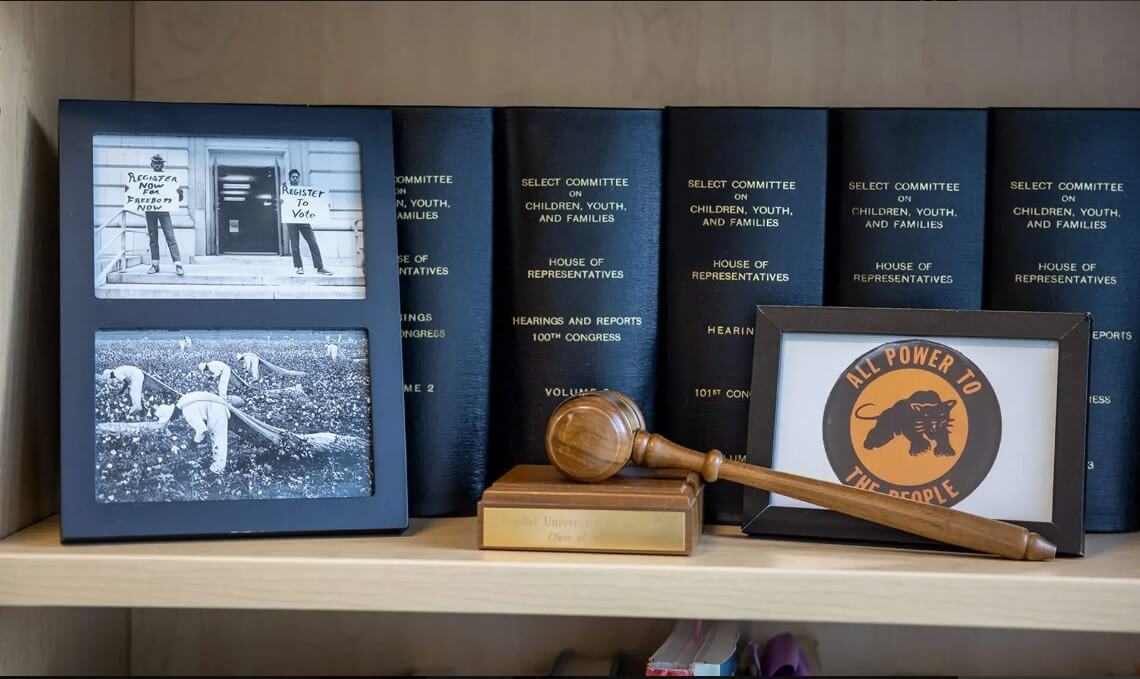

Records from Congress

The thick black tomes are records of testimonies and hearings from the House Select Committee on Children, Youth and Families. The late Pizzigati, a children’s advocate on Capitol Hill and beyond for nearly 40 years, was its last executive director.

“It speaks volumes that this committee doesn’t exist anymore,” said Slaughter. “There’s no one (in Congress) saying, ‘We need to pay attention to the kids.’”

Pizzigati’s UMD connection came through her Terps basketball fandom. She was a longtime booster of the women’s basketball program who became president of the Terrapin Club, so Slaughter takes the fellows to a game every year in her honor.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Children’s Defense Fund postcards and drawing

Slaughter calls the 1990s the “golden age” of children’s advocacy, when high-profile people like then-First Lady Hillary Clinton vocally supported the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) and the Children’s Health Insurance Program was launched nationwide. The black-and-white postcards are from a CDF campaign focused specifically on Black children.

“At the time, folks would say, ‘If we just do this great policy for kids, everybody will do well,’” she said. “But that’s not the case. You have to disaggregate the data, and you’ll see that children of color consistently have negative outcomes. This was the first time you saw the shift to, ‘How do we take care of the babies that are the most marginalized?’”

A drawing by Slaughter’s then-4-year-old neighbor, Lily, features prominently in the center. The colorful scribbles reflect the chaos of childhood and the clouds represent hope, Lily told Slaughter.

______________________________________________________________________________________

“The man in the arena”

When Slaughter was promoted to chief executive officer of Voices for Ohio’s Children, a nonprofit organization, her landlord gave her this gift.

“He had no idea it was my favorite quote!” she said. It’s a portion of President Theodore Roosevelt’s “Citizenship in a Republic” speech, given in Paris in 1910. It begins, “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena.”

Slaughter said, “This is what we try to teach our students. Pick your space, but do something. You can’t just sit back and complain. You have to be part of the solution.”