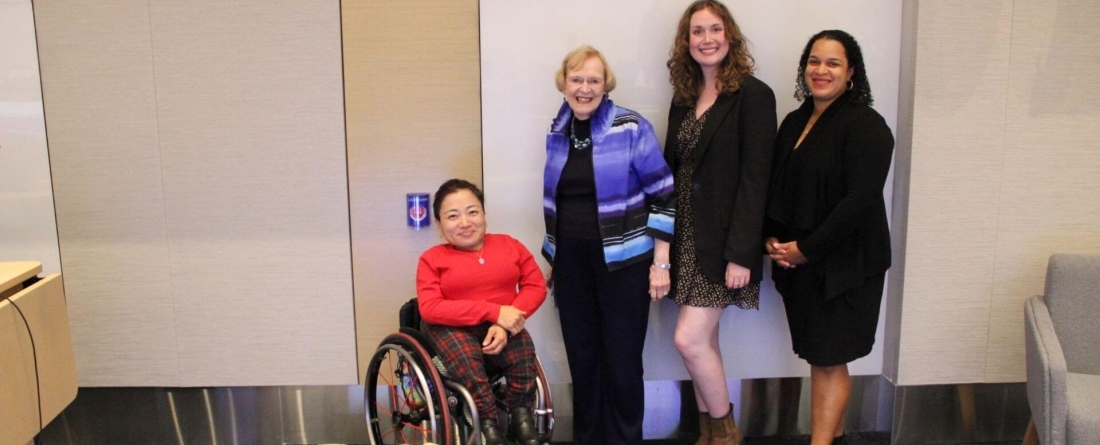

On Thursday, the Norman and Florence Brody Family Foundation Public Policy Forum featured a timely and thought-provoking discussion on advancing disability justice featuring prominent civil rights activist and advocate for disability justice, Mia Ives-Rublee.

Speaking in front of a packed house at the School of Public Policy, Ives-Rublee’s visit drew attendees from across campus eager to engage with her on the critical intersection of disability rights and public policy. Brody Professor Betty Duke delivered the opening remarks, introducing Ives-Rublee as a significant addition to University’s prestigious list of thought leaders who have spoken on pressing public policy issues over the years including writers, legislators, academics, media representatives and many others.

After her introduction, Ives-Rublee, a prominent voice in the disability rights movement, shared her compelling journey and lifelong commitment to civil rights activism. As a disabled transracial adoptee, her personal experiences have informed her advocacy work, providing a unique perspective on the challenges faced by disabled individuals.

After Ives-Rublee's presentation, the event transitioned seamlessly into a moderated discussion with Professor Alana Hackshaw, who serves as the chief diversity and inclusion officer at SPP. The evening concluded with engaging questions from the audience.

In her address, Ives-Rublee shed light on the prevalence of disability in the United States, noting that approximately 26% of the adult population in the country identifies as having a disability. “Within the last couple of years, we've added 2.7 million more disabled people into the population of adults,” cited Ives-Rublee. She attributed this increase to factors such as the impact of long COVID, the aging baby boomer generation and challenges in the healthcare system.

Ives-Rublee explained the different models of disability – the medical, structural and identity models. She emphasized the need to shift away from the medical model, which frames disability as an individual deficit, and instead adopt the structural model, which recognizes that societal barriers contribute to disability. Additionally, she introduced the identity model, acknowledging the importance of cultural awareness, experiences and societal perceptions in understanding disability. “We come from a vast variety of experiences,” acknowledged Ives-Rublee. “It’s important to take that into account when we are addressing the structural barriers within society.”

During her address, Ives-Rublee delved into ableism and intersectionality. Ableism, she explained, is a form of discrimination and social prejudice against disabled individuals that permeates public policy and society, affecting decision-making at federal, state and local levels. Intersectionality, she continued, is a lens through which individuals can understand how power dynamics intersect and affect people differently based on their multiple identities.

Ives-Rublee traced the history of the disability rights movement, highlighting its roots in the civil rights movement, particularly with the involvement of disabled veterans returning from war. These early activists collaborated with various civil rights organizations, including feminist groups and the Black Panthers, to fight for equal rights and inclusion.

Ives-Rublee points out that disability and ableism affect everyone, and they are not confined to medical or educational domains. Disability permeates all aspects of life, and everything in turn influences the experience of disability.

She highlighted pivotal legislations such as the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, which each marked significant milestones in securing basic rights and accessibility for disabled individuals. “Before 1973, disabled people weren't seen as whole human beings. There were things called the ugly laws, which basically stated that if you had a disability, you weren't ‘normal.’ You didn't have a job, then you were seen as a menace to society. And you were put into institutions,” Ives-Rublee revealed. “This particularly affected black and brown individuals who also had disabilities. And it was a significant issue for individuals because they couldn't get jobs. They were often left in institutions, and left to die there.”

I got to see my mom spend hours of her day fighting with teachers, with therapists, with principals, telling them that I deserve the right to 1) take classes with my classmates, 2) go on field trips, and 3) participate in after school activities.Mia Ives-Rublee

Ives-Rublee was six years old when the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed in 1990. Speaking of her admiration for her mother's relentless efforts to secure her inclusion and participation in school and community activities, Ives-Rublee shared, “One thing I got to see that was really inspirational to me … I got to see my mom spend hours of her day fighting with teachers, with therapists, with principals, telling them that I deserve the right to 1) take classes with my classmates, 2) go on field trips, and 3) participate in after school activities.”

Drawing from her personal journey, Ives-Rublee described her transition from being adopted from South Korea to becoming a policy analyst and disability advocate. “As an individual who grew up, who was born an orphan, who came to America, and who dealt with discrimination as a disabled person, I knew that I wanted to give back to my community. … It was a really interesting time for me to develop a sense of ideals and a sense of morals towards what I utilize today and my analysis of my policy work right now.”

Ives-Rublee introduced the concept of disability justice to the attendees, a framework that seeks to address the intersection of disability with other forms of oppression and places a strong emphasis on community wellness alongside policy advocacy. She explained that disability justice emerged in response to the limitations of the Disability Rights Movement, which often centered on specific identities and relied heavily on legal strategies. Disability justice advocates for a more inclusive and comprehensive approach to dismantling structural barriers in society.

Ives-Rublee left the audience with a powerful message: to embrace their own identities and prioritize self-care, emphasizing the profound significance of self-acceptance in the pursuit of justice. “It’s ok to be ourselves and it’s ok to take time for ourselves.”

With her unwavering dedication to disability justice and strong background in grassroots organizing, Ives-Rublee stands as a prominent figure in the fight for equal rights and inclusion for individuals with disabilities. Her work continues to inspire and drive change on both local and national levels, amplifying the voices of marginalized communities and pushing for a more equitable society where every individual, regardless of their background or abilities, can fully participate and thrive.